Close Encounters

“No one needs a rhino horn but a rhino.”

- Paul Oxton

Featured and published in Earth.Org and Paw Trails Magazine.

Mfalme translates to “King” in Swahili and a fitting name of this 35-year-old southern white rhino. His presence is commanding, given his immense stature and size of horn; very little can steal our gaze at this moment. His curiosity and sharp sense of smell brings him closer to the vehicle, compensating for his poor eyesight.

Located in a heavily protected private sanctuary in Central Province of Kenya, Mfalme shares his habitat with hundreds of black and white rhinos in a 20,000-acre reserve. Solio Game Reserve was created in 1970, one of the oldest privately owned rhino sanctuaries, boasting the largest rhino population in a single conservancy in the world – and growing.

(Existential) Threat of the Unicorn

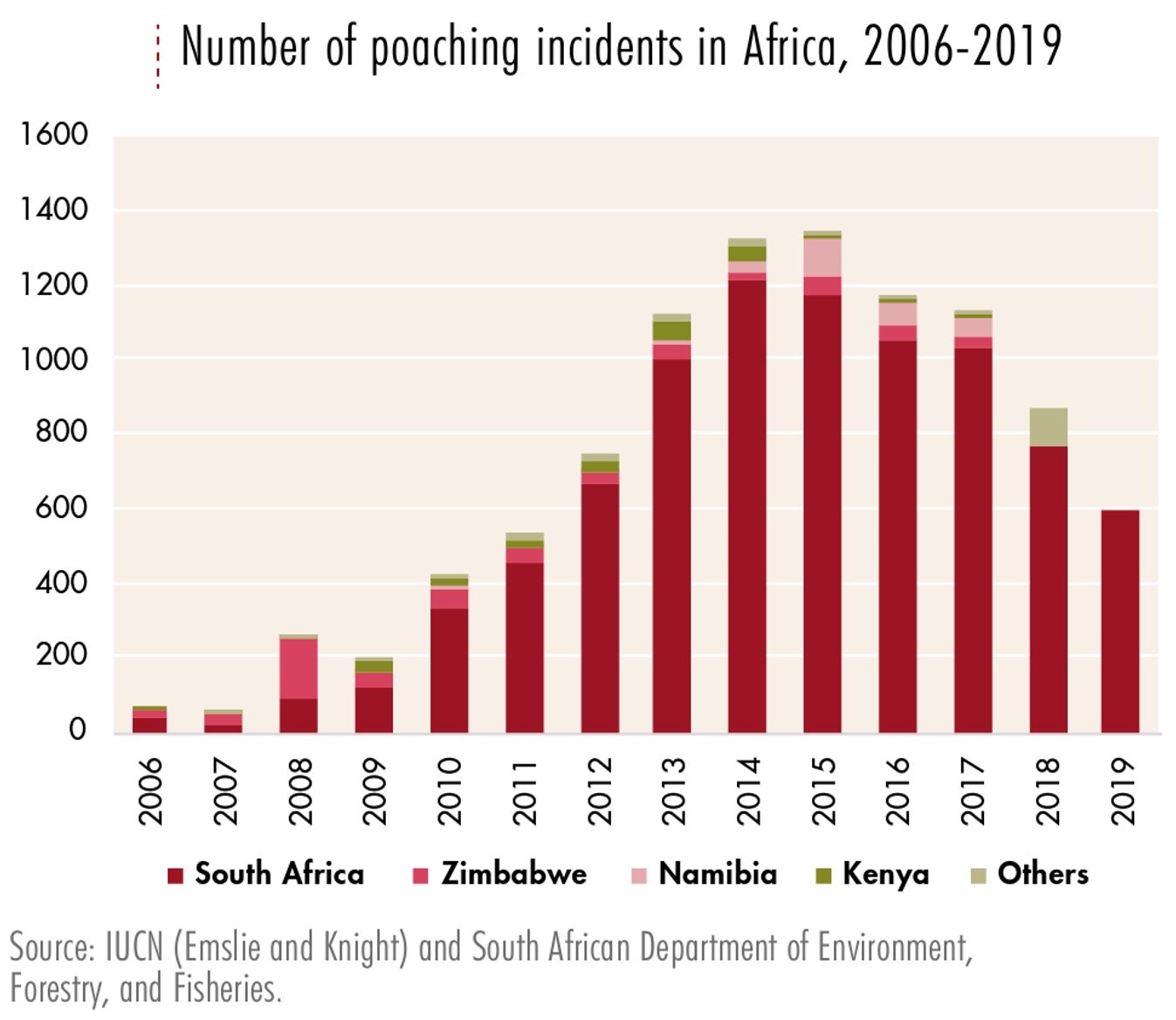

Unfortunately, the wider story is not so pretty. Based on the current and official poaching statistics, it is estimated that at least one to two rhinos are killed every day in Africa.

The readers of this article probably know very well that the primary threat to rhinos’ existence is poaching. It is well documented through investigative journals, reporting, and research undertaken by conservation related organisations and select media outlets. Well-known conservation photographers and videographers provide a visual story, which are often hard to watch, given the gruesome nature of the act. However, these types of visual exposures are necessary. A quick Google search on rhino poaching will yield over two million results.

Despite this, poaching remains the number one existential threat to rhinos. Why? The short answer is that the addressable (black) market of the rhino horn is huge.

Although rhino poaching in Africa has dropped since its peak in 2014/15, when almost 1,400 rhinos were poached, in 2019 an estimated 600 rhinos were poached – still an incredibly high number. It is worth noting these are officially reported figures; some countries do not release these statistics; hence the figure is likely more. About 90% of all rhino poaching takes place in South Africa - understandably as the country has the world’s highest rhino populations. It also borders Mozambique, where much of the rhino horn is smuggled through to its final destination in East Asia.

The black-market commercial value of rhino horn is somewhat of a sensitive topic as there are mixed opinions about publicising the value so as not to entice new market entrants, amongst other reasons. Some say that the value is not where the focus should be, but on helping the overall cause, which is true. However, we are humans – we are more likely to do something if we have a basic rational and quantitative understanding of the size of the problem. As such, and to give some context, today the value of rhino horn is worth more than gold, platinum or cocaine. Understanding the value of the rhino horn helps us to understand the size of this market. Using some high-level assumptions, the estimated calculations of the annual (black) market value of this illicit trade is in the region of US$200m – realistically, it is probably double this figure.

Put mildly, if this was a legitimate legal corporation, it would be a unicorn – a highly profitable billion-dollar company. THIS is the primary reason that poaching remains the number one existential threat to rhinos.

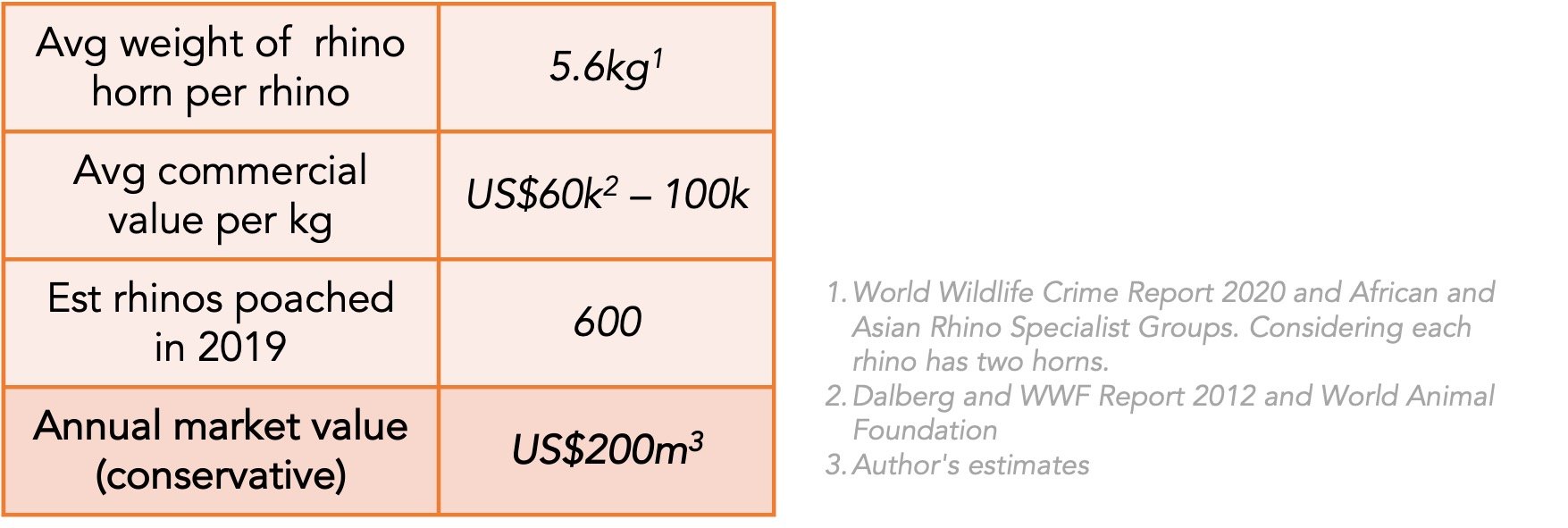

Many of us may not know this, but there are five species of rhino – today.

This may change over the next few years given the population levels of two species that are critically endangered. These are namely the Sumatran and Javan rhinos, primarily found in Indonesia. Collectively, there are less than 150 left in the wild and the species’ population continues to dwindle. Whilst poaching exists in this region, habitat destruction and climate change pose a larger threat. With such small and fragmented populations, breeding is increasingly difficult. The island’s natural habitat continues to shrink, as human populations continue to rise in the world’s fourth-most populous country. The space encroachment therefore is a key conservation challenge for long term survival for these rhinos. Sadly, both these species are quickly slipping toward extinction.

Javan Rhino in Indonesia. © Tobias Nolan

One horned rhino in India. © Patrice Correia

The third species is the Greater One-Horned rhino, found in India and Nepal. Although considered vulnerable by International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), this rhino has probably seen the most remarkable recovery. Hunted for sport and their horn, the Greater One-Horned rhino was close to extinction in early 19th century, with less than 200 remaining - today there are close to 4,000 rhinos thanks to conservation efforts and protected areas in India and Nepal.

The Black and White rhinos are the remaining species found in Eastern and Southern Africa. The Black rhino is typically more aggressive and considered critically endangered with an estimated 6,000 rhinos remaining. The White rhino is the biggest land mammal after the elephant and the most populous of the rhino species, with estimates of 16,000, down from around 18,000 in 2017, and considered near threatened by IUCN. About 80% of all black and white rhinos are found in various national parks in South Africa.

Whilst the Southern White Rhino is the more prevalent sub-species, the Northern White Rhino is critically endangered and considered extinct in the wild. There are only two individuals that remain, both female and residing in a protected sanctuary in Ol Pejeta in Kenya. They were brought in from a zoo in Czech Republic in 2009 to participate in a natural breeding programme; thus far is seeing some positive results. Led by a consortium of scientists and conservationists called BioRescue, several viable Northern White Rhino embryos have been created.

This is Najin, representing 50% of the population of Northern White Rhinos. Held in Ol Pejeta Conservancy, Kenya,

The Mafia of Rhino Horn

Organised crime (and this is exactly what it is) only flourishes in a corrupt environment – it is important to understand this. Combined with a market value exceeding US$200m, it is natural that many will be incentivised by the quick pay outs. The financial rewards are too tempting for impoverished locals residing near national parks, who will take up the role of Poacher or Broker. These are considered the Level 1 and 2 parties along the value chain. They work with the Level 3 stakeholder, the Dealer, who organises and finances the kill as well as maintaining a network of Brokers. Exporters and Importers are the next actor and the link between Africa and Asia, who provide full logistical support, from transportation by air or ship to customs on arrival to lining the pockets of numerous corrupt officials along the way in both African and Asian borders.

Source: World Wildlife Crime Report 2020

The destination for these high price items is East Asia, with Vietnam being a primary recipient. The rhino horns are distributed locally, as well as to China, who are known to generate the most demand for rhino horn and ivory – ever-increasing as populations and the burgeoning middle class continues to grow. The Wholesale Traders (Level 5) are the link between storage and distributing raw material to the underground retail market. Between them and the Level 6 Retailers, various products are produced to serve the high demand market in Vietnam, China, Hong Kong and Malaysia. They are sold to everyone from powerful kingpins and tycoons to government officials and diplomats and in the recent years, the emerging middle class.

Rhino horn seized in Hong Kong. © GovHK

The smuggling routes employed by criminal networks trafficking rhino horn are complex and dynamic, exploiting weaknesses in border controls and law enforcement capacity constraints to provide a steady supply of rhino horn to Asian black markets. They span countries and continents, passing through multiple airports and legal jurisdictions. It is a task made easier for criminals by fragmented enforcement responses hamstrung by bureaucracy, insufficient international co operation and corruption.

Status games: Rolex or Rhino Horn Powder?

Aged by old beliefs and a rising middle class across East Asia, a strong and growing market for rhino horn has been created and in turn a varied product offering. One such use is Chinese medicine or a miracle “drug”, one that is so versatile – everything from fever-reducer and hangover cure to cancer treatment, Viagra alternative and even COVID-19. There is no evidence to suggest any of these treatments work. A rhino horn is composed entirely of keratin – a protein that humans produce naturally found in our hair, nails and skin. This alone should diminish the belief that there is any medical benefit from rhino horn or at the very least use alternative sources for the active ingredient. Unfortunately, science, facts and common sense cannot topple the house of cards built on century old beliefs and traditions.

Finished products known to have rhino horn, seized by Hong Kong officials. © GAO

Status symbol is another reason behind the demand. It provides an opportunity for the affluent to display and mark their status, influence and power in a hierarchical society. Like many in the West would display their wealth with Swiss watches and overpriced sports cars, many in East Asian cultures view rhino horn and ivory as the ultimate status symbol. The end-product comes in the form of beads, bracelets, rings or carved ornaments to name a few.

As China and Vietnam are both state controlled regimes, a lack of and access to information plays a big role here. Generational and cultural beliefs still apply, with outdated and unproven hypotheses that are not questioned and hence followed blindly. The newly affluent are ready to splash out on ancestorial traditions and in some cases to quite extreme measures – there are stories of people selling their homes to acquire rhino horn or ivory.

Top Level Accountability

It is important to note that each party within the value chain plays a key role in the success of this illicit trade. Although they play an extremely important role on the ground, local rangers and conservation organisations alone will not make the ultimate difference; it is addressing the entire organised crime syndicate. We must do what we can to protect the species from poachers and their informants, but what needs to be addressed is the root problem – from the source of the demand to organised crime syndicates. Afterall, it is the demand that ultimately finances the entire operation.

Even with access to more reliable and accurate information, awareness campaigns and education, there is no simple overnight solution to change the perceptions of the end consumers; cultural and traditional beliefs will still linger on for a generation or two. Unfortunately, the species do not have this time. The average rate at which the rhinos are being slaughtered over the last decade is clearly unsustainable. With continued poaching rates, combined with destruction of habitat and climate change, it would not be surprising if only a few hundred rhinos are left in a decade, if that.

Whilst there is much to do in stopping poachers, educating local communities and attempting to break aged beliefs, the key stakeholder that has the power to severely disrupt this value chain is the government – both African and East Asian governments. Although there is a world-wide ban on poaching and illicit trafficking, it is clear the systems in place are not working – probably deliberately. It is easy to label this as corruption and this word tends to be thrown around a lot, generalising that the entire government is this way, especially in Africa. In fact, it is likely a few individuals that have found a loophole that they can take advantage of for financial gain and power. The people at the top have the power and ability to create change – but they have to want to. The leaders of the China and Vietnam governments could make a huge impact with very little resource and financial investment to clamp down corrupt custom officials, underground retailers, enforce bans and hefty fines, as well as implement accessible information and educational resources.

A Bright Spot: Solio Ranch

Originally a cattle ranch, Solio Game Reserve was formed as part of a conservation effort initiated by the owners, The Parfet Family. They apportioned a huge part of the land for conservation and breeding of rhinos, in particular the threatened black rhino. It was the first of its kind in Africa with an ambitious objective to protect and breed rhinos, given rhino poaching was increasing at a rate that would surely wipe out the species in Kenya. Black rhino populations in Kenya dropped from around 18,000 in the late 1960’s to less than 1,500 by 1980 and about 400 in 1990. The Kenyan Government in the 1970s supported and helped with the protection of the sanctuary with the Kenyan Armed Forces as well as Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS).

Rhino being reintroduced in the 1970’s. © Solio Game Reserve

Despite the downward trend, this small unknown conservancy was quietly fostering populations of both black and white rhinos. By the mid-1980’s, the conservancy had to be expanded due to concerns of overpopulation. Eventually Solio Game Reserve

became a primary breeding ground, supplying national parks all over the country including Lewa, Lake Nakuru National Park and Ol Pejeta, as well as helping to restock populations in Southern and East Africa. One can trace most black rhinos in Eastern Africa back to Solio Game Reserve – this is impact.

Rhino orphan feeding time in the 1970’s. © Solio Game Reserve

This conservancy has not gone by without its own challenges. The early 2000’s saw a rapid spike in poaching in the area and in particular targeting Solio Game Reserve. Along with protection from Kenyan Armed Forces and KWS, additional private anti poaching security was brought in. In 2005 they began a photographic database of all the rhinos that reside in the park to ensure that every animal is watched over and monitored. These efforts immediately made it close to impossible for poachers to breach and ensure long term monitoring programs were in place.

Solio Game Reserve plays a central role in the rehabilitation of the species in East Africa, boasting the most successful private rhino breeding reserve in the world which then helps to facilitate reintroduction of rhinos all over Africa.

“No one in the world needs a Rhino horn but a Rhino.”

― Paul Oxton

A fitting quote for what has been an emotionally difficult article to research and write, for the most part. Whilst some arguments may come across as disheartening, there are some bright spots and places in parts of Africa that are creating impact and making a difference – Solio Game Reserve is one such example. We may feel helpless, but by simply reading this article, you already have contributed to the cause – knowledge and awareness is the first step.